- Home

- Andrew D. Blechman

Leisureville Page 8

Leisureville Read online

Page 8

Lowering the age limit to fifty-five opens the market to a much larger demographic of potential buyers, especially if only one member of a household has to qualify. A sugar daddy can still live with a twenty-five-year-old wife or even a college-age child. And if the real estate market sags, a developer has the option of abandoning the eighty-twenty mix and opening up the properties to all ages.

To help justify the need for age restrictions, the amendments of 1988 to the Fair Housing Act required such communities to provide “significant services and facilities specifically designed to meet the physical or social needs of older persons.” The wording was somewhat vague, but the intent was not: retirement communities may exist because they cater to the special needs of their elderly residents. The Department of Housing and Urban Development came up with a long list of what serves these special needs, such as communal cafeterias, wheelchair accessibility, and specially designed athletic classes, but developers complained that these requirements were unduly onerous, especially for no-frills lower-income mobile home retirement communities. Congress scrapped this provision altogether in 1995 with passage of the Housing for Older Persons Act, and retirement communities no longer had to justify their existence.

Despite the amendment’s obvious drawbacks, the civil rights community nevertheless saw progress through the haze of compromise. Not only did the legislation require the federal government to strictly enforce the entire Fair Housing Act and pave the way for physically and mentally handicapped renters and homeowners; it finally addressed the plight of a previously ignored demographic—families with children. Even the choice of the relatively young entry age of fifty-five was seen as a small victory because the barrier age for many retirement communities, such as Sun City, was then just fifty.

The civil rights community had a particular interest in the legislation because it saw discrimination against children as a proxy for discrimination against poorer minorities in general, who often have large families. Minorities were routinely turned away from potential rentals on the pretext that children were not permitted. A study conducted at the time by the Department of Housing and Urban Development found that neighborhoods with a white majority were twice as likely as predominantly nonwhite neighborhoods to have anti-child housing restrictions.

Before the legislation, landlords, developers, and neighborhood covenants could arbitrarily discriminate against families with children. There was no federal law addressing this situation, and only a few states attempted to forbid such discrimination. It was not unusual for housing complexes to routinely charge higher rents for families with children, or forbid them altogether without cause. Moreover, couples could be evicted if the woman was pregnant.

The first language addressing age segregation in Youngtown didn’t appear in deed restrictions until 1975—much later than had been presumed. With an increasing number of young renters moving into the community, Youngtown city officials sensed trouble on the horizon. To neutralize the threat, the city council voted to officially incorporate age restrictions into the town’s bylaws. Nearly two decades after its founding, children were finally verboten, or so the town elders thought. They aggressively enforced the new law and evicted more than 100 families until their legal charade collapsed in the face of the attorney general’s finding in 1998.

The ruling hit the seniors of Youngtown hard. With the law no longer on their side, their humble paradise was inevitably going to be invaded by hordes of children. To add insult to injury, the state ordered Youngtown to pay Chaz’s family $30,000 in restitution. Although this was a meager amount under the circumstances, it was nonetheless seen as a princely sum for a troublesome brat. When news of the settlement was announced at a packed town meeting, it was greeted with an audible gasp, then silence. Sensing that things could soon turn ugly, the town attorney warned residents, “Retaliation … is a violation of state and federal law and will be prosecuted accordingly.”

Chaz and his grandparents moved out anyway. Chaz had been briefly celebrated in the media as the Rosa Parks for his generation, but he soon fled the spotlight. I was eager to speak with him on one of my trips to Arizona, but locating him proved to be quite a challenge. It was as if Chaz had simply vanished.

Even after I eventually located him, by means of an unlisted cell-phone number, it took numerous awkward calls to persuade him to meet with me. “That was a long time ago,” he complained. “I’m living a different life now.” When I told him that I came bearing greetings from Dan Connelly, Youngtown’s current police chief, who was an officer during the incident, Chaz began to relent. “The chief said he hoped your life was going well since the events at Youngtown, particularly because they should never have happened in the first place,” I told him.

Now in his mid-twenties and married, Chaz is the picture of earnestness. Still skinny as a beanpole, he is casually but neatly dressed when I catch up with him at a coffee shop in Phoenix. He wears his hair combed straight back, has a thin mustache, and wears eyeglasses.

“I don’t begrudge older folks who want to live alone together,” Chaz says, much to my surprise. “There’s a lot of crime and violence in today’s society. There’s no respect for old people anymore. They have wisdom and stuff to hand down to people. But kids today are unruly. The way kids are dressing, talking, and acting, it makes me feel like an old man. But people in general don’t care about each other any more. The world is a wicked, violent place. And it’s not going to get better until people start living the word of God. That’s the only real solution.”

Chaz informs me that he is now a Jehovah’s Witness, and spends much of his time knocking on doors bearing witness to the glory of God. He hands me a religious booklet titled “What Does the Bible Really Teach?” One illustration depicts an intercontinental missile circling the Earth and a crazed criminal holding a gun to victim’s head. The caption reads: “The casting of Satan and his demons out of heaven brought woe to the earth. Such troubles will soon end.”

As far as Chaz is concerned, Youngtown did two things wrong: it broke the law, and it didn’t show any sympathy for his family’s special circumstances. “I didn’t move to Youngtown because I wanted to; I moved there because I had to,” he tells me. “Things were really bad back home. It was an abusive situation. My grandparents pleaded with the town council. All they were asking for was nine more months. But the council wouldn’t budge. They didn’t show any compassion or mercy.

“What they were doing was illegal anyway. Youngtown wasn’t age-restricted; they were just faking it. If it had been legal, I would have left. I wasn’t about to chain myself to my grandparents’ house. I’d have gone back to live with my mom if I had to.

“It got real nasty. You’d think, being old people, they’d be more mature. I wasn’t a pristine kid in those days, but I was a still a nice kid. One neighbor said I was a real sweet boy. I didn’t go around vandalizing and creating havoc. I don’t see how I was such a hardship. I didn’t even hang out in Youngtown. I met my friends in Peoria. But I don’t think those old folks really cared whether I was a criminal or not. They didn’t want young people there, period. They didn’t want to get to know me.”

Given its close proximity, I asked Chaz if he ever visits Youngtown. “I go back sometimes,” he answers. “It brings back a lot of sad memories. I’d hate to see it happen to somebody else, another young person. I think there’s always room for compassion, for empathy for what someone else is going through. When I drive by Youngtown and see all the families, I can’t help thinking, ‘Is that because of me?’ And you know what? I won’t lie—I do like the fact that Youngtown is filled with young people.”

* * *

Youngtown’s transition into a multigenerational community was awkward, to say the least. The town had no schools or playgrounds, and the library, well stocked with large-print books, had no children’s section. “We don’t have the land or resources to build these things,” the mayor at the time said. “Youngtown is an island. It was never designed fo

r children.” The police chief was equally perplexed —what would happen to the seven PM curfew for visiting children? “We used to pull over a carload of kids because they didn’t belong here,” he said. “Now they might be residents.”

In many ways, Youngtown before Chaz was already a dying town on the wrong side of the tracks from Sun City. Many of Youngtown’s residents were doing their best just to hold on. The geriatric community reinvested little to nothing in its public structures and common areas, let alone its private residences. Its businesses left, residents of Sun City avoided it, and the nation forgot its historical significance.

Ask anyone to name America’s first retirement community and the answer will probably be Sun City. It was Del Webb on the cover of Time, not Ben Schleifer. And it was Sun City that grew and grew, while Youngtown stagnated. Schleifer said his biggest regret was that Sun City wasn’t at least ten miles away so that his community wouldn’t have to be compared with it.

But after years of stasis and benign neglect, the housing market was opened up to everyone. Young families flocked to Youngtown for many of the same reasons its older residents had come: crime was negligible, homes were unusually affordable, and taxes were incredibly low—Youngtown doesn’t tax its residents, but relies instead on state revenue sharing and a local sales tax. Once Youngtown was thrust into the greater real estate market, its artificially low property values shot up more than thirty percent practically overnight, and well over 200 percent in ten years. Many seniors chose to sell their homes at a handsome profit.

As Youngtown’s aging retirees died or fled across the street to Sun City, the town filled up with young families. The retirees and their treasured traditions were fast disappearing, swallowed up by youth culture, much as everywhere else. Boom boxes blasting rock and rap replaced tabletop radios playing golden oldies; children’s shrieks and teenagers’ shouts replaced gentle greetings; and complaints about kids playing in the street fell on deaf ears. The Saturday dances, barbecue picnics, and quiet strolls were a thing of the past, replaced by a lingering fear that crime would soon threaten whatever remained. A deep well of resentment grew between the generations, who interpreted the name “Youngtown” to mean different things.

Desegregation has never proved to be an easy undertaking, and integrating Youngtown had its own particular challenges, many of which were lost on the newcomers. To the seniors the issue was simple: they didn’t want younger people around. But to the newcomers, discrimination based on age was probably a difficult concept to understand. After all, a white person can’t have been born black, but everyone was once young.

The seniors suffered yet another perceived indignity when the young invaders flexed their political muscle and elected one of their own as mayor. A youngster born after 1960 would now govern the veterans of World War II and Korea. The new mayor arrived at his first council meeting riding a Harley-Davidson, and gunning the engine for effect. He immediately set about carrying out his campaign pledge to spend more money on the town’s children by building playgrounds, athletic fields, and a skateboard park.

Meanwhile, a group of seniors worked to discredit the mayor, much as they had done before with Chaz. They dug up and circulated damning court documents, but this time the documents were real and the mayor was guilty as charged. To Youngtown’s older residents, the crime could hardly have been more emblematic of their predicament: the mayor had once been arrested for parking in a space reserved for the handicapped—albeit thirteen years earlier and halfway across the country. Worse yet, unlike the town’s penny-pinching elders, the young mayor proved to be a profligate spender, and many people blamed him for draining the municipality’s reserve funds.

Given Youngtown’s tumultuous recent history, it’s somewhat surprising how little its historic center has changed when I visit. Compared with old photographs I had seen, it looks much the same as it did decades ago, with a bandstand in the middle of a modest green, and a one-story town hall that originally served as housing for ranch hands. Across the way is the town library, where there are now children’s books as well as computer terminals popular with Youngtown’s teenagers.

Farther down the street is a small playground and just beyond that is Maricopa Lake, which resembles a retention pond. But any amount of water in the desert is a luxury, and this tiny body of water is no exception. At the far end is a picnic gazebo and a few scattered pieces of old playground equipment. Lake or no lake, the heat and dust never let you forget where you are.

Many of Youngtown’s streets sweep around in the lazy curves that characterize so many subdivisions today. The homes that are well maintained are charming in the suburban style of the 1950s: ranch houses with small footprints, little carports, and carefully manicured gardens. But there are also plenty of run-down homes with ratty yards, peeling paint, and tinfoil hanging from windows to keep out the searing desert sun.

The commercial area is still recovering from the exodus of businesses in the 1970s and 1980s. The town’s big grocery store left in 1978; and a cooperative failed, owing to a lack of volunteers. I see two massage parlors and a tattoo business. Across the street, Sun City and its palm-studded boulevards beckon.

The most radical new addition to Youngtown is also the one that is most difficult to access. One either has to drive halfway around the edge of the community or across a steep and creepy (at least at night) storm wash to reach a subdivision called Agua Fria Ranch. The development represents the community’s first substantial residential construction since the early 1960s, and it is a source of great pride. The subdivision looks much like any other—uninspired homes with large garages facing one another—but there are plenty of basketball hoops and children playing in the streets.

Much of the subdivision’s infrastructure—such as flood control —was paid for with a $3 million special assessment for which only those living in the new development are responsible. The assessment’s purpose is to make sure that the residents of “old Youngtown” don’t have to pay for improvements exclusively designed for residents of “new Youngtown.”

On my way out, I spy one homeowner participating in an activity feared and despised by most deed-restricted communities, including old Youngtown. His car is hoisted up on a jack in his driveway, and he is buried somewhere under the chassis, presumably changing the oil. In many of the communities that I have visited, such activity is quickly reported and the perpetrator is warned to refrain from it in the future or face expulsion. Most members of a homeowners’ association will tell you that taking a hard line is necessary to keep a community from spiraling downward.

Nonetheless, Agua Fria is considered a complete success, because it quickly doubled the town’s population, from 3,000 to 6,000. It also balanced out the community’s lopsided demographics. There is now the same number of younger people as older people, although time is ultimately on the side of the town’s younger residents.

Graffiti is not altogether rare, and according to Dan Connelly, Youngtown’s sixty-five-year-old police chief, crime has indeed increased since desegregation. The department recently added a drug-sniffing dog to the force, to help deal with a growing problem: methamphetamine. But the crime is due to a number of factors, Connelly tells me.

When it was first built, Youngtown was more than thirteen miles from the city limits of Phoenix. The retirement community and its neighbor, Sun City, were islands of green in a vast expanse of desert. But as Phoenix rapidly grew from a small city to a sprawling metropolitan area—it is now the fifth-largest city in America—it expanded to within three miles of their boundaries. One look outside at the congested roads makes the region’s inexorable growth abundantly clear.

“At this point, we’re really just another bedroom community of Phoenix,” the chief tells me when we meet. “In ten more years we’ll be considered inner-city. We’ve got all the crime and the problems that other cities have.”

But while Youngtown has its share of drive-through crime, he says that much of its criminal activity is

now homegrown—just as the obstinate seniors angrily predicted it would be. “We used to get about two domestic violence calls a year,” says Connelly. “Last year we had 337. Ages twenty-five to forty are the prime demographic for domestic violence. In general, we have the same number of calls for service today as we did in 1999. But they’re no longer Mildred calling because she can’t find her cat or can’t figure out how to operate the air-conditioning now that her husband’s dead.”

Another measure of change is the so-called death patrol. “We used to collect thirty-five to forty dead bodies a year; now we find ten, if that many.” As the town’s demographics change, so does its sense of community. Requests for the death patrol now come from concerned relatives “back home” rather than from a neighbor. “It’s usually some nephew from Canton, Ohio, asking us to check up on his uncle who turns out to be dead on the toilet,” Connelly says.

And yet, the chief tells me emphatically that the increase in crime has been worth the sacrifice. “Look, where you have kids and young people, you’re going to have problems. But on the flip side, we now have a vibrant, growing community. We even have a kids’ soccer league. As far as I’m concerned, the banning of children was wrong. I don’t see it as being any different from the overt prejudice against African-Americans in pre–civil rights America. When I was in the military, I was stationed in the South, and I remember that time well.”

In his view, integration has actually led to better relations between the generations. To illustrate this point, the chief recalls an incident from the mid-1990s, just before age restrictions were lifted: an older woman ran over and killed a seven-year-old girl who had just gotten off her school bus. “The woman was angry. She told me that the child should never have been crossing the street, because schoolchildren aren’t allowed to live in Sun City. That’s how bad it was.”

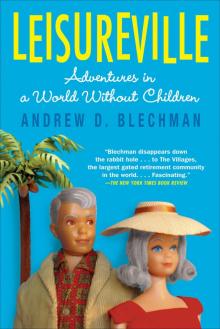

Leisureville

Leisureville