- Home

- Andrew D. Blechman

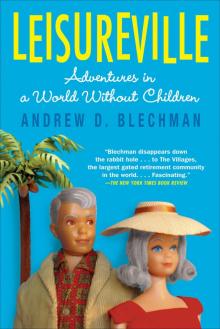

Leisureville Page 3

Leisureville Read online

Page 3

Dave puts the windshield down on the golf cart and flips on the headlights. He drives down the curving streets and then passes through a tunnel. We glide past golf carts traveling in the opposite lane. The sensation is oddly thrilling. Cruising along in a golf cart at twenty miles per hour is somehow more invigorating than traveling in a car at seventy. Occasionally a speedier souped-up golf cart flashes its turn signal and passes us on the left. Golf cart headlights and red taillights are all around us, traveling in a silent and orderly fashion, like a video game with the sound turned off. Dave has a smile plastered to his face, and so do I. We look at each other and chuckle with amusement.

At dinner, I notice that the entrées on the menu are surprisingly affordable, as if early bird prices are a permanent fixture, and it’s always happy hour somewhere in The Villages. Many of the people I meet carefully adjust their weekly schedules around happy hours with free appetizers and two-for-one drinks.

After dinner, we stop on a balcony to admire the setting sun. “Quite a sunset,” I remark.

“A lot of them are,” Dave responds.

“There’s no place I’d rather be,” Betsy says. “This is home.”

“Gosh, what a day,” Dave continues. “A bad day here is better than a good day at most other places. Oh, well, I guess some of us are meant to suffer, and some of us aren’t.”

“That sunset is pretty as a picture,” Betsy says.

“It’s more like a postcard,” Dave counters.

“I say picture. It’s just like a painting you’d hang on a wall,” Betsy says.

“No, it’s definitely a postcard,” Dave says. “But you’d need a wide-angle lens to capture it.”

I look out over the championship golf course with its undulating carpet of green, punctuated by palms that stir in the mild breeze. Across the way is yet another golf course, this one designed by Arnold Palmer. In the distance I see a cluster of homes big enough to be classified as McMansions, but designed for very few occupants—a retired couple, perhaps, or a widow.

Dave is in as good a mood as I’ve ever seen him, as if a huge burden had suddenly been lifted from him. He is positively light on his feet as we leave the country club. To my astonishment, he grabs an antique light pole near the door and swings—yes, swings—around it. He even attempts to kick up his heels like Fred Astaire.

Back home, Dave generously gives me keys to the house and a guest pass, which allows me to use many of the amenities, such as family swimming pools. To obtain a guest pass, Dave had to register me with The Villages, and my birth date and other information rest in their computer system. Non–family members, like minors, are permitted to visit for only up to one month a year.

Since each visitor is registered and handed a bar-coded pass, it would be difficult to overstay one’s welcome, as access to all amenities would be denied. In effect, my guest pass is a visa that entitles me to experience The Villages’ lifestyle, but like most visas, it also expires. This is one way The Villages keeps tabs on minors. But it’s the residents themselves who generally keep a close eye on occasional scofflaws: a youngster wearing a school backpack has little chance of escaping the attention of one’s neighbors.

Dave also hands me his and Betsy’s “calling card.” Villagers have revived a quaint tradition that seemingly died out not long after the time of Edith Wharton and Henry James. Instead of business cards, many Villagers carry cards that list their name and village. The Andersons’ also displays a 1950s-era image of a man and a woman swinging golf clubs.

As Dave and Betsy wind down for the night, I head out in search of nightlife. As I drive off, smoke sputters out of the exhaust, and the loose muffler roars. There’s oil splattered on the street, but thankfully, none on Dave’s driveway.

Spanish Springs is buzzing with people of all ages strolling along the sidewalks. A group of giggling retirees walk past me wearing giant sombreros and carrying oversize cocktails in their hands. They tell me they are on a scavenger hunt. A friend shouts greetings to them from a restaurant patio across the street.

A crowd has gathered around the center gazebo for the nightly bread and circus of free entertainment and inexpensive drinks. The band’s front man is wearing faded jeans and a blue blazer. A partially unbuttoned shirt reveals a forest of glistening blond chest hair. He hops around the gazebo with his cordless microphone, pointing this way and that as he sings the chorus, “God is with me, yeah!” He then breaks into a rendition of Chuck Berry’s classic “Johnny B. Goode,” descends from the podium, and starts mingling with his audience of boogying grandparents and shrieking grandkids, several of whom jump up and down in their motion-sensitive sneakers with blinking red lights.

I chat with a man named Joel who moved to The Villages shortly after turning fifty-five. “I love it here,” he tells me. “The neighborhoods are neat and clean. We’ve got covenants here and they’re enforced, which is good, because they keep out the riffraff.” Joel, however, ran afoul of one of The Villages’ deed restrictions: lawn ornaments are prohibited in many neighborhoods. “It was just a boy and a girl holding hands,” he explains sheepishly. It wasn’t even two feet tall. I got a knock on the door the very next day. It’s my own fault—I should have known better.”

The band finishes its final set and the audience clears out. Empty drink cups litter the ground. The nightly cleaning crew silently picks them up and collects the 100 or so folding chairs. One of the crew, a stocky man with a thick southern drawl peculiar to rural Florida, approaches me. “Shit, these old folks do more drinking than them college kids. And that’s a lot. They got nothing else to do. You watch.”

I head across the street to the last place open in Spanish Springs: Katie Belle’s. There’s nobody at the door to check my resident ID, so I just sneak in. A country and western band is onstage playing one of Shania Twain’s hits. The dance floor is packed with older couples, dressed casually in shorts or jeans, swaying back and forth. Some are wearing sandals with athletic socks. Although my outfit is somewhat par for the course around town, I nevertheless resolve to leave my sweater vest, loafers, and argyle socks at home next time. I belly up to the crowded bar and order a draft. It arrives in a mug that looks heavy, but out of consideration for the older clientele is made out of plastic and is light as a feather. To my surprise, a bartender announces last call moments later. I look at my watch: it’s nine forty-five.

An older man taps me on the shoulder and asks if he can borrow my pen. He holds it carefully in his arthritic hand to take down the phone number of a woman wearing bright red lipstick. He returns a few minutes later to borrow the pen once again, to jot down another woman’s phone number.

I introduce myself to two guys farther down the bar who look to be in their mid-twenties. They’re brothers, they tell me, visiting from Iowa, where their mother used to live before she packed up and moved to The Villages. Carl, the younger brother, gulps down several shots of tequila lined up in front of him. He sports a goatee and a baseball hat with the brim squeezed into a tight semicircle. He spots my notebook and pen.

“You writing a book?” he asks. I nod. “It’s a good thing, because this place is fucked up!” His brother, Ben, nods in agreement. I ask them if their mother is happy here. “She misses some things,” Carl says.

“Like what?” I ask.

“Home.”

They invite me to the equivalent of after-hours in The Villages—a late-night karaoke bar inside a bowling alley. It’s just outside Spanish Springs in a strip mall that is also owned by The Villages. The facade is designed to look like the Alamo, and it’s called, not surprisingly, the Alamo Bowl. It is one of two thirty-six-lane bowling complexes built for residents so far: one smoking, the other nonsmoking.

The three of us squeeze onto the front bench of their mother’s golf cart. Ben unrolls the cart’s plastic siding to protect us from a nippy wind, while Carl whips out a six-pack from a cooler behind the seat. We each pop open a beer. Carl flips on the battery, and the cart shoots forward

. “Golf carts are definitely the way to go,” he says. “You can drink and nobody screws with you.”

Outside the Alamo Bowl, the parking lot is filled with golf carts, four to a space. “Bowling alley bars suck dick,” Carl offers, then pops open another beer. We step inside the karaoke bar, a popular Mexican-theme place called Crazy Gringos. It’s full, and we struggle to find seats. An older woman with a bright red sweater and skinny legs is singing “Tainted Love.”

We pull chairs up to a crowded table and I’m introduced to Jan and Darryl. They were neighbors when Carl and Ben were growing up in Iowa and remain good friends with their mother. Now they live in The Villages, too. Several pitchers of beer arrive. Carl leaves to sign his name on the karaoke list. Jan turns to me, asks if I’m looking for a “sugar mama,” and winks. With her short hair and bouncy energy, she passes for younger than her seventy years.

As is often the case when a Villager greets a stranger, the conversation veers to life in The Villages. “You can be anyone you want to be here,” Jan says. “If you ever, in your younger years, wanted to play softball, be a pool shark, or twirl a baton—maybe you weren’t any good at it, or didn’t have the time to do it—well, you can do it now. After living here, Darryl and me, we’re not going back to Iowa. The kids are there and all, but we’re not going back. It’s too friggin’ cold.

“This place is so unique. You can’t really compare it with anywhere else. Anything you need or want; it’s just a golf cart away. It’s unreal. And you don’t have to be fifty-five to enjoy it—well, you do if you want to live here—but it’s fun for everyone. My kids love visiting. Heck, my daughter would move in tomorrow if she were old enough. We were in a rut back in Iowa. But we’re here now, and it’s a party place. It’s been like a vacation from day one.”

Darryl looks at me with rheumy eyes. “I don’t say a lot,” he says, slurring his words. “But I like it, too. I just want to spend my days here; the ones I have left.”

Onstage, Carl is singing a rap song about big butts and getting “some booty.” I’m surprised to see several younger men on the dance floor make like they’re having sex from behind with their young dates. Then it’s back to the golden oldies with Elvis’s “Can’t Help Falling in Love,” and the dance floor fills up again with inebriated seniors. “They play anything from the 1950s or 1960s and the floor is packed,” Jan shouts over the music. “That’s the age group you got here.”

Several drinks later, I stagger to the toilet, passing alongside the closed bowling lanes. Once there, I bump into a man wearing a Veteran of Foreign Wars baseball cap. “I was a marine at Guadal-canal,” he says, and then lets out an impressively long belch. “I was wounded there and now I have diabetes. But after all these years, at least I can still party at The Villages.”

3

The Golden Years

RETIREMENT IS A RELATIVELY NEW PHENOMENON. FOR THOUsands OF years, with a few exceptions, humans would simply work until they couldn’t. People lived in extended families because they needed to do so: survival generally required a collective effort. Parents worked hard to raise their children, and as they aged and their health faded, the roles were reversed, with elders relying on their children to care for them.

Beginning about a century ago in America, our growing prosperity made other living arrangements possible. The middle class gained enough of an economic foothold for the elderly and their adult children to consider establishing separate households: why live crowded under one roof when a family could afford to spread out in several homes? Then came the Great Depression, which—among other things—wiped out the pensions and savings accounts of many of the nation’s older citizens. With unemployment at all-time highs, young families, who could hardly support themselves, were once again forced to care for their elders.

Social Security was in part designed to humanely pull older workers out of the workforce so that unemployed younger workers could fill their jobs. But it also shifted much of the economic burden of caring for elders away from individual family members and onto society as a whole; seniors now had a safety net.

The covenant implied in Social Security is deceptively simple: you pitch in now for today’s senior citizens, and subsequent generations will pitch in to keep you from abject poverty. As my yearly Social Security statement explains: “Social Security is a compact between generations.”

The first checks from the Social Security Act of 1935 were cut in 1940. The original payouts were rather small, more of a contribution than a real replacement for income. Because the age requirement was sixty-five years and the average life expectancy was then only sixty-two, few Americans at that time lived to see their check from the government.

But in time, rapid medical advances and the economic stability afforded by generous company pensions as well as monthly Social Security checks led to the creation of a whole new class of people—retirees.

What was retirement supposed to look like? What were these retirees supposed to do with the few remaining years during which they were viewed as too old to work, but too young to die? Mass retirement was a new phenomenon with few guidelines to follow. To many, the word “retirement” itself had a negative connotation, implying that seniors were being taken out of circulation, like old horses that were no longer useful.

As the extended family continued to disintegrate and the nation became infatuated with a youth-centered culture, seniors were left to chart their own way. Few knew what to expect from these years besides loneliness, declining health, and possible abandonment in “God’s waiting room”—a gloomy nursing home. To some, retirement might as well have been a death sentence.

Out of this anomie, a new idea began to take shape—the creation of communities where active seniors could live together, free from the confines of dreary old-age homes. Although religious and fraternal organizations flirted with the concept of retirement communities as early as the 1920s, the nation’s first age-segregated community was not built until the 1950s. It was called Youngtown, and it was little more than a modest housing development with a clubhouse in the middle of the Arizona desert. But its elderly inhabitants were grateful for it.

According to Youngtown’s founder, Benjamin “Big Ben” Schleifer, its inspiration was an old Jewish prayer: “Do not forsake me, God, when I get old.” Schleifer says he first heard the prayer as a youngster living in a shtetl outside Minsk, where his father worked as a timber surveyor. In 1914, the Schleifer family fled czarist repression and Cossack raids, and immigrated to America.

In New York, the thirteen-year-old Schleifer skipped school and went to work as an errand boy. An avid reader, he says he educated himself with discarded newspapers that he found on the subway. He eventually held a succession of jobs: farmhand, textile mill worker, flour miller, and grain broker. In the late 1940s, a bout of asthma forced him to relocate to Arizona, where he began to dabble in real estate, often unsuccessfully. He formed Big Ben Realty and worked out of an office not much larger than a phone booth.

Homesick for the east coast, Schleifer returned several times in the hope that Arizona had cured his asthma. He had no such luck, but one trip back east proved to be fortunate. He visited a friend in a nursing home in Rochester, New York, and was struck by the man’s frustration with the regimented and confined lifestyle. Schleifer thought he could do better. He committed himself to building an entire community devoted to retirees and resolved to call it Youngtown, so that it “would be associated with youth and ambition.” He wanted “to make elderly people not feel old.”

In 1954, Schleifer bought a 320-acre desert ranch about twenty miles from downtown Phoenix, which was then a small city. At the time, an older widow and her 175 head of dairy and beef cattle were all that populated the land. To save money, several of the original ranch buildings were incorporated into Schleifer’s new community. The milking station became the hobby shop, and housing for the ranch hands became the town hall. “My idea was to keep the costs down,” Schleifer said at the time. “I did

n’t build a community for millionaires. Millionaires can go to Bermuda.”

By most accounts Youngtown was a success: Schleifer had created a place where the blunt indignities of old age were softened, at least for a time. People came from all over the snowbelt for the warm weather and fellowship. And, more important, they didn’t come to die; they came to live.

There were games of canasta, potluck picnics, garden clubs, and Saturday night dances. Residents staged musicals, pitched horseshoes and learned to tap-dance. Crime was practically nonexistent, and taxes were impossibly low. It was like one big family, albeit a family without children to disturb the peace and quiet of the blissful desert idyll.

Within a year, 125 homes had been built and eighty-five of them had been sold. Soon, enough homes were built that businesses opened up to serve the new residents. In contrast to friends they left back home—many of whom were slowly atrophying in nursing homes—Youngtown’s pioneers considered themselves fortunate. In 1960, optimistically, Youngtown incorporated. A nascent American Association of Retired Persons selected the community as the site of its first chapter. Membership cost twenty-five cents.

The philosophical underpinnings of Schleifer’s preference for age segregation were more practical than purposefully discriminatory: children cost money. A community without kids is a community without schools and with no high taxes to pay for schools. One of Schleifer’s main objectives was to ensure that Youngtown’s residents could afford to live with dignity, even if their sole income was Social Security.

“Nature divides the generations,” he said. “So let’s not blame the older people for not wanting children in the community. We didn’t build Youngtown for social advancement. We built it for the economic security of the elderly.”

Leisureville

Leisureville